Chapter One

The first time I met my uncle Lucas I tried to steal something from him. It’s ironic, really, considering what he would ask me to do twenty-six years later.

I was seven, on a visit to London with my mother and my father, Lucas’s younger brother. We’d been travelling through my father’s native England on holiday from our home in Australia. I was too young to realise the trip was a last-ditch effort to keep my parents’ marriage afloat. Perhaps I should have guessed. Since we’d flown from Melbourne airport two weeks earlier, they hadn’t stopped fighting.

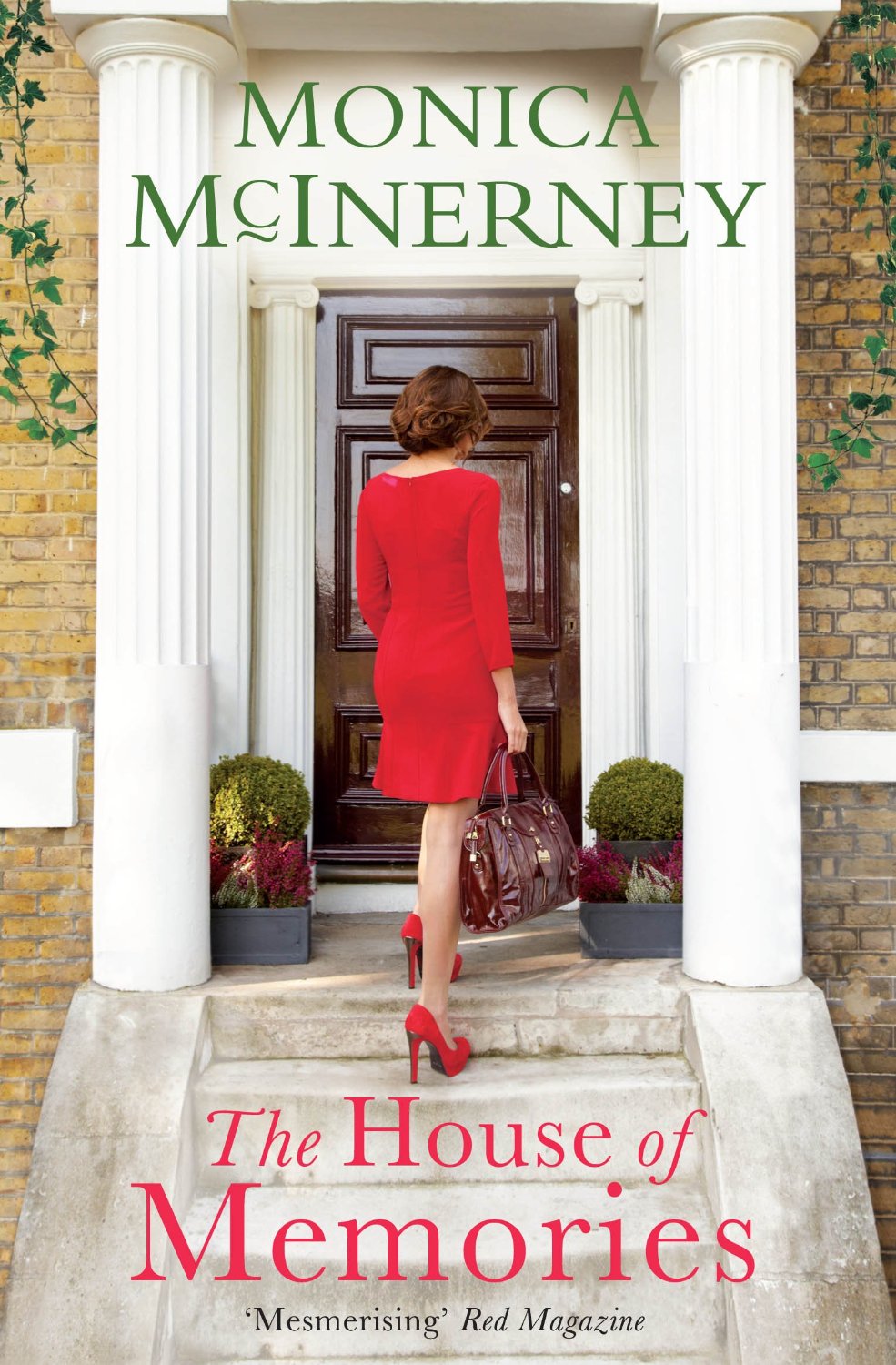

Lucas lived in a three-storey terrace house in west London, not far from Paddington Station, two blocks in from the Bayswater Road and close to Hyde Park. Not that I knew any of those landmarks then. I remember wondering who had to mow all the grass I could see through the park gates, and thinking the houses looked like wedding cakes. I also remember running up and down the steps outside Lucas’s house while we waited for him to answer our knock.

I was an only child at that stage, and was used to adult attention, but I was also used to living in the shadow of my parents’ arguments. I think they were fighting when Lucas opened the door. Not physically, just the usual exchange of well-crafted, well-spoken insults. I remember Lucas running a hand through his thick mop of brown curls and saying in his lovely deep voice, ‘Still at it, you two?’ before getting down on his haunches, looking me right in the eye and saying with a big smile, ‘Hello. You must be Arabella.’

‘Ella,’ I said firmly. Even at that age, I hated my full name.

‘Ella,’ he said. ‘Much nicer. Do you know what that is backwards?’

I nodded. ‘Alle.’

He held out his hand. ‘Hello, Alle. I’m Sacul.’

We followed him in, Dad and Lucas already in conversation, my mother trailing behind and complaining about her aching feet, caused by the high heels she’d insisted on wearing, though we were having a sightseeing-around-London-on-foot day. That might have been what she and my father were fighting about on the doorstep. Or it could have been any of a thousand other things. I was ignoring the adults by now, in any case. I was too busy looking around.

My parents had been here the previous year, visiting Lucas while on one of my father’s many business trips abroad. I’d not gone on that trip, remaining in Australia in the care of a family friend. My father worked in the mining industry – as an accountant, not underground – often travelling to the various locations owned by his multinational employer. Sometimes during school holidays Mum and I travelled with him. So I was used to staying in big hotels and luxurious apartments. But no place I’d seen compared to this house.

It wasn’t the high ceilings, the long hall, the staircase, the many doors, the fabric wallpaper or the books everywhere that grabbed my attention. It was the mess. The place was filthy. Not only that, there wasn’t a bare surface to be seen. Boxes overflowing with paper littered the hallway, producing a kind of maze effect. One long wall was lined with bookshelves reaching from floor to ceiling. Each shelf was so jammed it would have been difficult to slide in a pamphlet, let alone another book. Perhaps it smelt musty and unclean in reality, but in my memory it smelt of paper and old books and even wood smoke. A barbecue? I wondered. No. I could see there was an open fire in a room off the hallway. A fire in summertime!

Just before Uncle Lucas ushered my parents into what he jokingly called the withdrawing room, he turned and handed me the key of freedom.

‘Go wherever you like, Ella. Touch whatever you want. Just try not to break anything.’

I took off. He barely had time to offer my parents a cup of tea before I was back.

‘There’s someone in that room,’ I said, pointing across the hallway.

‘Male? Red hair? Glasses?’

I nodded.

‘That’s Bill. One of my students.’

‘Is this a school?’ I asked. ‘Are you a teacher?’

‘Two excellent questions, Ella. No, not exactly. And no, not exactly.’

My father explained it more later, on the way back to our hotel in a taxi. (My mother had complained so much about her feet that we’d given up the plan to go walking and sightseeing.) Lucas was the brainbox of the family, my father told me. Honours in history at Cambridge. Groundbreaking research since. He was working on a new academic study, but in the meantime, he’d also thrown open his house to bright but impoverished students to live and study in.

‘His house?’ my mother sniffed. ‘It should have been your house too.’

‘His godfather left it to him, Meredith, not me, as I’ve told you a thousand times. And as I’ve also told you, I never wanted it, or needed it.’

‘It’s not about needing it. It’s the principle. It should have been divided between you. But no, you just let him have it. Because your problem is you’ll do anything to avoid confrontation.’

My father ignored her and looked out the window.

‘It’s the waste of it that gets me,’ my mother continued. ‘He’s sitting on a real estate fortune, and what does he turn it into? A commune for pointy-heads.’

I didn’t know any of this as I first walked around the house that morning. All I got was a little jolt of excitement each time I opened a door to discover a student in a room. There was one in the kitchen, one in the front room, two upstairs and one on a kind of balcony at the back of the house, overlooking a small, overgrown garden. I counted five students, male and female, all either reading or scribbling or, in one case, measuring out liquid from one glass jar into another in the bathroom. If my memory serves me right, that particular student went on to work for NASA. All of them pretty much ignored me.

‘I’m Lucas’s niece,’ I said each time.

‘Hi, niece,’ was about as interactive as one of them got.

I did as I’d been told and roamed everywhere, through all three storeys. At the very top of the house I found the best room of all. It was a converted attic, with a sloping roof, bookshelves everywhere, and a kind of alcove in the corner where I could see an unmade bed, a lamp and more books. On the floor, a pile of notebooks with Lucas’s name scrawled on the covers confirmed that this was his part of the house. In the centre of the room, not pushed against the wall like my father’s desk was in our Melbourne home, was his desk. It was as large as a dining table. And it was – like the rest of the house – covered in stuff: bundles of paper, folders, boxes, books. And more books. Every surface in the room was covered in books. And in any of the gaps left, there were foxes. Dozens of foxes.

My full name back then was Arabella Louisa Fox. Mum and Dad were Meredith and Richard Fox. Which meant, of course, that my uncle was Lucas Fox. He must love his surname as much as I do, I remember thinking. I ignored the books and started counting the foxes. There were seven framed paintings of foxes on the sloping walls. Five little statues of foxes on top of the cupboards and tucked into the bookshelves. A fox pattern on a lampshade. What looked like a candle holder with a brass fox at the base. And on the desk, right at my eye level, was a real fox. A real, baby fox.

There wasn’t much light in the attic. None of the lamps was on, and the overhead light was turned off. The only light came in through the roof window. It seemed to shine directly on the golden-brown fur of the baby fox, highlighting the glorious reds of its tail, sending a spotlight onto its little face and a gleam into its small, bright eyes. Eyes that were looking right at me.

‘It’s all right,’ I remember saying, edging towards it. ‘I won’t hurt you.’

I reached out and patted it gingerly, waiting for the snap of teeth, even while I hoped for a kind of purring sound. Did foxes purr? I wondered. The second I touched it I knew that it wasn’t real. Or at least, it was real, it had been alive, but it wasn’t any more. Its head was cold and still. Its back cold and hard. I ran my fingers along the fur. Several strands came off. I looked into its eyes. And whether it was because I was tired, or because my mum and dad fighting had left me jittery as it always did, I don’t know; suddenly that small dead fox on the desk made me sadder than I had ever been in my life.

‘You poor little thing,’ I whispered to it. ‘You shouldn’t be here.’

There was a piece of material on the floor, a length of curtain or an old dust sheet. I picked it up. I wrapped the baby fox in it. I put the bundle under my arm. I don’t know what I thought I was going to do with it, or how I’d slip out of the house without my parents and uncle noticing. It was summer and I was in a light dress, so I couldn’t even hide it under my coat. But I just remember feeling so protective and so sad, all at once. I was on a mission now. I was Ella Fox, Fox Rescuer.

I heard raised voices as I came down the stairs. My mother, then my father asking her to please mind her own business, then Lucas saying something I couldn’t hear, then my mother again. I’d thought this was a friendly visit. Perhaps it had started that way. I didn’t stand there, as I often did at home, eavesdropping. I slipped out through the front door. I wasn’t running away, not really. I think I only wanted to give the little fox some fresh air, a brief taste of freedom.

But Uncle Lucas didn’t know that as he looked out the front window. All he saw was his seven-year-old niece heading down his steps with a fabric-wrapped bundle under her left arm, the tail of a fox sticking out of it.

Afterwards, Mum told me they’d thought it was very funny.

‘You certainly broke the tension, Ella,’ she’d said.

Lucas appeared at the front door just as I reached the bottom step. ‘Ella?’ I stopped at the sudden sound of his voice, low and calm. ‘Are you stealing my fox?’

‘No, not exactly,’ I said, unconsciously echoing his own words from earlier.

‘No? Then what, exactly?’

‘It looked lonely up there,’ I said. ‘I was taking it for a walk.’

My father appeared beside his brother. ‘It’s dead, Ella. It’s a stuffed fox.’

‘It looked lonely,’ I repeated.

‘Inside, Ella. Now,’ my mother said, appearing at Lucas’s other side. ‘Give Lucas back his fox.’

There was no more fuss made than that. In retrospect, they probably wanted to get back to their argument. I returned the fox to its home in the attic and patted it goodbye. I was about to kiss its little snout too, but then I caught sight of its tiny sharp teeth. I still felt sorry for it, but it had also started to give me the creeps.

We said goodbye to Uncle Lucas soon after.

‘Well, that was pointless,’ I remember my mother saying as our taxi pulled away.

‘What was pointless?’ I asked.

‘Never mind,’ my parents said as one.

I thought they meant Lucas was pointless, and I didn’t think that was nice. ‘I liked him,’ I said, turning to gaze out the window, more wedding-cake houses on one side, the big park on the other. ‘Him and his foxes.’

A month later, back home in Australia, I’d received a parcel in the mail, postmarked Paddington, London. Inside was a letter from Uncle Lucas, complete with a footnote.

My dear FLN*

I’m so sorry I couldn’t let you keep the fox that day. It’s very precious to me. But I hope this little one will give you some pleasure. It’s also a bit easier to smuggle out of people’s houses.

Love from your London uncle,

Lucas

*Fox-Liberating Niece

It was a tiny gold fox on a key ring, just an inch long, but beautifully made, the detail of the fur and the fox’s features delicately done. I called it Foxy. Foxy the Fox. At first I carried it in my pocket as a good-luck charm, whispering to it whenever I was upset or if Mum told me off about something. Once I was old enough to have keys, it turned back into a key ring. Over the years, it had held keys for many houses, in different cities of Australia, in London and in Bath. The last time I had seen it was in Canberra nearly two years ago. I’d left it, with the apartment keys, on the kitchen table beside my farewell note to Aidan —

Stop!

Change your thoughts.

Look forward.

It’s always easier said than done. I’ve tried everything in the past twenty months – snapping an elastic band around my wrist, inhaling essential oils, meditation. I tried concentrating on my surroundings now instead, a suggestion I’d recently read in a book on managing difficult memories. Focus. Notice. Distract. Observe. I mentally listed everything I could see around me, forcing myself to take note of my surroundings, to be fully aware of where I was and what I was doing at this exact moment.

I was on the Heathrow Express. I had just flown twenty-two hours from Australia to London. My handbag was on my lap. The seat in front of me had a blue fabric cover. The carriage was packed with fellow travellers, some with eyes shut, others yawning, each of us recovering from our flights in different ways. I looked over at the luggage rack, checking if my red case was still there. It was. I stared up at the small TV screen on the far wall of the carriage. It flickered from the news headlines to a weather update. The forecast for London was a cold, breezy February day. The ticket collector appeared beside me. Good, another distraction. I handed my ticket across, watched him briskly stamp it and then move on to the next passenger. I turned back to the TV. ‘We are now approaching London Paddington,’ a bright English-accented presenter announced on-screen. ‘Thank you for travelling with Heathrow Express.’

I’d arranged to visit Lucas at two p.m., the earliest I thought I’d be able to make my way from Heathrow to his house. It wouldn’t be the first time I’d seen him since the day of the fox liberation, of course. The letter he’d sent with Foxy was also just the first of hundreds – literally hundreds – of letters, faxes and emails he’d sent me in the years since. From the moment we’d met, without either of us realising it, Lucas had become the most reliable adult in my life.

Three months after that first visit to London, my mother and father told me they were getting divorced. Irreconcilable differences. I’d had to learn how to say and spell irreconcilable. It was a nasty divorce. They’d fought through their marriage and they fought through their divorce: over the division of their assets, over who got the house and who got me. After legal action that lasted more than a year, Mum won most of it, our small house in East Melbourne and me included. The last time I saw Dad was the day he came to tell me that he’d been offered a job in Canada and had decided to take it.

Eight months after the divorce became final, my mother married again, to a German businessman called Walter she’d met at a garden centre. They’d both reached for a large terracotta pot at the same time. When she would retell the story in the many magazine articles about her in later years, she would say it was Cupid at work – Walter’s surname was Baum, the German for tree, and they’d met in a garden centre! That terracotta pot led to coffee and on to a series of secret dates – she’d told me she was going to night classes. ‘I didn’t want to get your hopes up until I knew for sure myself,’ she said. I hadn’t had any hopes. I was still getting used to Dad being gone, not wishing for a new father.

They had a small wedding. It was my stepfather Walter’s second marriage too, so neither of them wanted a big fuss, they said. Walter came complete with a large bank account, his own stockbroking business, a lot of silver hair, a beard, a big house in Richmond and a son, my instant stepbrother, Charlie. (Full name Charlemagne. Truly.) He was two years older than me, eleven to my nine. Charlie’s mother had gone back to Germany to live after the marriage ended. She wasn’t well, my mother told me. Certainly not well enough to look after Charlie. Mum tapped her head and did a kind of rolling thing with her eyes as she told me. It took me a while to realise she meant Walter’s wife wasn’t well in her head. It was years later before I learned more about her. Neither Charlie nor Walter mentioned her much in the early days.

And so the two of us joined the two of them and we became four. Less than two years later, three weeks after my eleventh birthday, four turned into five, with the arrival of a baby girl called Jessica Eloise Faith Baum.

‘We’re a proper family now,’ my mother said. I remember wondering what we’d been before.

She also told me that she was changing my name by deed poll to Baum. ‘It’s too confusing otherwise,’ she said. ‘And we should all have the same surname.’

‘But I like being Ella Fox,’ I told her.

‘You can keep it as a middle name,’ Mum said. ‘You might as well have some reminder of your father. It’s not as if he goes to much trouble to keep in touch any other way.’

She was right, unfortunately. Dad rang only occasionally from Canada. He sent me Christmas presents and birthday cards that mentioned me visiting him in his new home, but the visits never happened. Mum didn’t speak of him at all if she could help it. When she was with her friends, she referred to her first wedding day as The Big Mistake Day. None of their wedding photos was in the house. They’d somehow been left behind when we moved in with Walter and Charlie. So had all the other photos of Dad. If it hadn’t been for Uncle Lucas sending me a replacement set of photos (at my request), I’d have forgotten what my father looked like. Lucas and I had become occasional penpals since we met that day in London. I liked having a penpal on the other side of the world, especially one who was related to me.

A month after I turned twelve, it was Lucas who rang with the news that my father had been killed in a light-plane crash in Ontario. He wrote to me afterwards. My dear Ella, he said. I know you hadn’t seen your father in some time, and I also know he was sad about that. And I know that you have a new father and indeed a whole new family now and I hope all is well. But if you ever need some advice from your Wily Old Fox of an uncle, please send me a letter or a fax (I have just installed a very smart-looking fax machine) and I’ll get back to you as quickly as I can.

I wonder whether Lucas had any idea what he might have unleashed with that simple, kind note? From that day on, he became my combination agony uncle, imaginary friend and sounding board, all via the wonders of a fax machine.

My stepfather worked from home sometimes, and he had all the basic office equipment in his study. I’d watched him send a fax one day and thought it was the most amazing thing. He noticed my interest and let me send the next one for him, instructing me in his exact, near-perfect English. That was always when Walter and I got on best, when he was teaching me something and I was being obedient in return. Outside of those times, I think we did our best to ignore each other. It was easy enough to do without any feelings being hurt – my mother kept up such a constant stream of chatter and opinions that she papered over any silences or gaps in our relationship. And of course Walter had Charlie to talk to, in English and German, and then baby Jess as well. His real children. Looking back now, I realise it was hard for him too, and for my mum, with not only a new baby, but a new stepchild to get used to. But back then, I just felt lonely and sad a lot of the time. Like that baby fox in Lucas’s office.

Two nights after I got Lucas’s letter, while Mum and Walter were out at a work dinner and Charlie, Jess and I were being babysat by our middle-aged neighbour (who always turned on the TV as soon as my mother and Walter left), I tiptoed into the office and switched on the fax machine.

I decided to copy Lucas’s straight-to-the-point style of communication.

Dear Uncle Lucas,

I need your advise. (Spelling wasn’t my strong point back then.) I don’t feel virry happy. I have a new baby sister but she crys all the time and Mum likes her more than she likes me.

What should I do?

Your neice,

Ella

I carefully keyed in the long fax number Lucas had included with his letter, fed in the paper and watched it go, holding my breath. I sent it a second time just to be sure. And a third time. Five minutes later, I was sitting in Walter’s chair, chewing the end of my ponytail and swinging my legs, when the fax machine began to make a new noise. I watched, wide-eyed, as a piece of paper started to move of its own accord, go through the roller and appear in the tray. I picked it up.

Dear Ella,

She’s a baby. Babies cry. That’s their job. Give her time to grow up and get interesting, then decide if you like her or not. And I’m sure your mum loves you both. That’s her job.

He’d not signed it, but underneath the writing was a little drawing of a fox. A cheeky fox, with a glint in its eye.

I took out a fresh piece of paper from Walter’s stationery drawer.

Thank you. I will wait.

I signed mine with a little drawing of a fox too, except my fox looked more like a skunk. I fed it into the machine and carefully pressed all the numbers again. Off it went. A few minutes later, another whirr of the machine and a new piece of paper appeared.

You’re welcome. Underneath it, another fox. This one was winking.

I took all the faxes into my bedroom and read them once more before I went to sleep, feeling much better. In the morning, I put them away carefully in my treasure box.

The next day after school, Mum called me into the kitchen. ‘You really shouldn’t use Walter’s fax machine without asking, Ella.’ Before I had a chance to speak, she went on. ‘There’s no need to look so cross. Lucas wasn’t telling tales. He rang to ask permission to send you faxes occasionally. Walter and I have discussed it. As Walter said, he is your only uncle. So as long as you don’t get too carried away, you can fax Lucas now and again and he says he’ll get back to you as soon as he can. But don’t annoy him, will you? He’s a very busy man.’

That surprised me. ‘Is he? Doing what?’ All I could picture Lucas doing in that big London house of his was making a mess.

‘I don’t know exactly, Ella. Professor-y things.’

‘But what kind of things?’

Mum waved her hands in a ‘I can’t even begin to explain’ motion. ‘Ask him next time you fax him.’

So I did. Lucas faxed back the very next day.

Dear Ella,

This week I am busy studying the following subjects:

Political allegiances in post-war Britain

Trends in liberal versus conservative educational policy

The rise in pro-monarchist sentiment between WWI and WWII

I also need to get the plumbing in the downstairs bathroom fixed.

I faxed back. Thank you, Lucas. You are very busy.

As a bee, he said in return. Or a fox. He signed it with that winking fox again.

It was like having a hotline to heaven. I faxed Lucas at least twice weekly and he always faxed me back. Except of course we called it foxing, not faxing. They weren’t long letters. Questions or minor complaints from me, usually. Quick answers or snippets of information from Lucas, or one-liners that he called Astounding Facts of a Fox Nature. Did you know that baby foxes are called kits, cubs or pups? Did you know that a female fox is called a vixen? Did you know that a fox’s tail makes up one-third of its total length?

Occasionally a present would arrive in the post. Not at birthdays or Christmases, but out of the blue. Always something to do with a fox, of course. A T-shirt with a fox on the front. Fox notepaper. A fox brooch once. I either used, lost or grew out of everything, except the fox key ring.

He sent books too. I am a crime aficionado, he said in one note, and you seem like an inquisitive young lady, so I hope you will enjoy this genre too. I did, reading every one that he sent – from Enid Blyton’s Secret Seven, Famous Five and Five Find-Outers series, to Nancy Drew and The Hardy Boys, to Agatha Christie’s novels. As I got older, Lucas sent books by Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett and Arthur Conan Doyle. An Astounding Fact accompanied every one: Did you know Enid Blyton wrote eight hundred books in just forty years? That Agatha Christie also wrote romances under the name Mary Westmacott? That Raymond Chandler only started writing detective fiction in his mid-forties?

Jess was too young to care then, but Charlie was always curious about my faraway uncle. Not jealous. Even back then, Charlie was the most even-tempered, laidback person I knew.

‘Any new facts from the fox?’ he’d ask.

I’d go to my Lucas folder and read out the latest fax. Charlie was always very impressed.

I didn’t send Lucas any astounding facts in return, but I did send him regular updates on school results or any academic prizes I happened to win.

Your father would be proud of you. I’m proud of you, he’d fax back.

We didn’t meet in person again until I was twenty-two. After finishing an Arts degree, I’d decided to take a gap year. I’d studied English literature, my father was English, I had a British passport – I headed straight for London. When I emailed Lucas (we’d progressed from faxes) to tell him I was coming, he insisted I stay with him until I found my feet. He was still in the same house, which was still full of bright but financially impoverished student lodgers, but he was now more than their innkeeper. He’d become their employer, setting up a discreet, high-level pool of personal tutors. It worked in everyone’s favour, he told me. His lodgers always needed extra money. Struggling school students always needed extra tuition. Well-off parents were always happy to pay. A win-win-win situation.

I stayed for a month that first time and loved every minute – his house, the tutors, the city, Lucas himself. The following year, I returned and stayed for six weeks. After that, I visited as often as I could. I’d pay my own airfare after saving every cent I could from my new, full-time job in a Melbourne publishing house, supplemented by my evening job as an English tutor. Lucas’s tutors had given me the idea. I steadily rose through the ranks at the publisher, from editorial assistant to copyeditor to editor. At the age of twenty-eight, single and restless, I resigned from my job, packed up my flat, said farewell to my friends and family and flew to London, yet again. I worked for Lucas as his cook and housekeeper for two months before I found a short-term job as a badly paid editor with a literary magazine in Bath. I still travelled back to London most weekends and stayed in Lucas’s house each time, going to the theatre or, more often, staying in and cooking dinner for him and whichever of the tutors happened to be in the house. Which was how, where and when I first met Aidan.

Two years later, on a sunny Canberra afternoon, Lucas was the witness at my registry-office wedding to Aidan Joseph O’Hanlon, originally of Carlow, Ireland, lately of London and now of Australia. Aidan and I had moved to Canberra a year after we met, when he was offered an interpreting and translating position with the trade commission there. He was fluent in French, Italian, Spanish and German. I’d gone freelance, able to work as an editor from anywhere.

It was important to us both that Lucas was at our wedding. He’d brought us together, after all. My mother was vaguely friendly to Lucas, I think. Marriage to Walter had softened her or at least helped her forget how annoyed she’d once been with my dad and, by extension, Lucas. Walter made stilted conversation with him, as Walter tended to do with everyone. Jess pretty much ignored him. Aged nineteen, she was too busy flirting with the young guitarist we’d hired to provide background music at the reception. Charlie was living in Boston by then, happily married and about to become a father for the fourth time. I knew he was sorry to miss meeting Lucas and Aidan, and especially sorry to miss our wedding.

Aidan and I didn’t go on honeymoon until Lucas returned to England. We spent the week after our wedding playing tour guide with him, visiting the galleries and museums in Canberra, driving up to Sydney and down to Melbourne. Lucas and I had been close before my wedding. We became even closer afterwards. After Lucas went home, Aidan and I headed off on our official honeymoon – two weeks in the US, spending several days, of course, with Charlie and his family, including his new baby son. Aidan and Charlie liked each other immediately. They were both clever, gentle men, so I’d hoped and expected it, but I was still relieved.

Back home in Canberra, work and everyday life took over from weddings and travel. I emailed Lucas as regularly as ever, about authors I was working with, or asking his advice about points of grammar. I told him about Aidan’s job. Lucas told me he had a full house – six lodgers, the most ever. More clients than he could supply tutors to, as well. I fear for the future of this once great country, but rejoice in my rising bank account, he said.

Less than six months after the wedding, the news that Aidan and I were having a baby unleashed a torrent of one-line Astounding Fact emails from him. He continued to send them all the way through my pregnancy. Did you know that the first sense a baby develops is hearing? That a baby is born around the world every three seconds? That a baby is born without kneecaps?

When I emailed five hours after the birth (long and painful, both facts immediately forgotten) to tell him we’d decided to call our newborn son (big, healthy, so so beautiful) Felix Lucas Fox O’Hanlon, I heard nothing back. I was too exhausted and too dizzy with love to mind, I think. Perhaps he was away. Two days later, there was a knock at our Canberra apartment door. Aidan told me the postman could barely carry the parcel inside, it was so huge. It was a five-foot-high toy fox. Thank you, Lucas’s handwritten note said. I am overjoyed for so many reasons.

After that, Lucas started writing to Felix more than me. I pretended to be hurt, but I loved it.

Dear Felix, he would email, How is the sleeping going? Have you been told that Felix is the Latin word for lucky or happy?

Felix wrote back to him too, of course, channelled through me or Aidan. He was very articulate for a baby and very appreciative of the new series of Astounding Facts for Infants.

Dear Lucas,

Yes, I am sleeping and also feeding very well, thank you for asking – I have already put on 800 grams. Thank you also for the link to the Large Hadron Collider website. I look forward to seeing it for myself one day.

Love for now from your grand-nephew, Felix.

We sent Lucas dozens of photos of Felix. Lucas sent Felix books. Boxes of them. Not just picture books, either. He sent Dickens, Tolstoy, Austen, Homer . . . His goal, he told us, was for Felix to have a complete library of the classics by the time he started school. At the rate the books were arriving, Felix would have had a full library of the classics by the time he started kindergarten. For Felix’s first birthday, Lucas sent him another five-foot-high toy fox. To keep the other fellow company, he said.

A month after that, Lucas surprised us – delighted us – with a spur-of-the-moment visit to Canberra. He stayed for less than a week, too short, but enough time for us to take dozens of photographs of him and Felix together. Serendipitously, his visit coincided with one of Charlie’s trips back to Australia. The two of them met for the first time. They clicked immediately.

I can still picture one afternoon in particular. We were having an informal lunch at our apartment, the balcony doors wide open, the sun streaming in, a light breeze in the air. There in our small living room were my four favourite people in the world – Aidan, Lucas, Charlie and Felix. There was a moment, a beautiful, sweet moment, when I took a photograph with perfect timing: Charlie making a corny joke, Lucas throwing back his head and laughing, Aidan smiling and shaking his head, and there, in Aidan’s arms, Felix, giving his big, gummy, delighted smile and kicking his legs at the same time, as if the smile alone wasn’t enough to signify how much fun he was having. In the photograph, his legs are just a blur. At the time, I remember a feeling, like a dart of something, that felt like light, a warm feeling, a rush of it. I realised afterwards it was joy.

After Lucas went home again, the emails between him and Felix increased. There were intense discussions about communism versus capitalism and the merits of cricket compared to football. The books kept arriving. Poetry from Byron, Yeats and Wordsworth. The Spot books. The Mr Men tales. Lucas was no literary snob. Aidan had to put up another bookshelf in Felix’s room. Felix emailed Lucas to say thank you and to remark that his bedroom looked more like a library these days.

Wonderful! Lucas emailed back. A boy can never have too many books. Wait till you see what I’m sending you for your second birthday . . .

But then —

When —

Afterwards —

After it happened, as soon as Lucas got my message in the middle of his night, he wrote to me. On paper, not by email. It arrived by courier. One line of writing, on thick parchment paper, with the fox drawing on the letterhead.

My dearest Ella, I am devastated for you both. I am here if you need me. Lucas.

It said everything I needed to hear. It made me cry for hours. I had already been crying for hours.

Almost twenty months had passed since that day. I wasn’t arriving in London unannounced. Lucas had emailed a fortnight earlier: Where are you now, Ella?

I was in Margaret River, in Western Australia. My contract as a casual worker at one of the largest wineries in the area was up. I’d been offered an extension but I was ready to move. Since it happened, I hadn’t stayed anywhere for long. I’d left Canberra within weeks. I’d moved to Melbourne, then Sydney, before I’d heard about the winery job. I’d been there since.

I’d like to see you, Lucas had written. Please let me buy your airfare.

I wanted to see Lucas too, but I didn’t need his help with the airfare. I’d saved every cent I’d earned. There was nothing I wanted or needed beyond the basics. I booked my ticket the next day. It felt exactly the right thing to do, after months of feeling like I was living in fog.

Even flying into London that morning had felt right. Because I thought being here again might help? Because I had loved it once, and had been happy here? I think I hoped that being back would help me or force me to feel something other than despair.

Come and see me as soon as you get here, would you? Come straight from the airport.

Lucas wasn’t being mysterious. He was always matter-of-fact like that.

You do know you are welcome to stay for as long as you need to? Mi casa es su casa.

My house is your house. He had said that to me many times over the years. To his many student lodgers as well, I knew. Aidan had always laughed at his terrible Spanish pronunciation. Lucas was a genius historian but a bad linguist. Thank you, Lucas, I wrote back.

I walked the short distance from Paddington Station to his street. Twenty-seven years had passed since my first visit to Lucas’s house. He’d been in his mid-thirties then. He was in his early sixties now. Yet he always looked the same to me. I was the one who’d changed most over the years, from that seven-year-old fox-stealing curly-haired child to the thirty-four-year-old woman I now was. I’d been a tall, skinny child. I was still skinny, still taller than average. My dark-brown hair had been long until a year ago. I’d cut it two days after I arrived in Margaret River and kept it short since.

The houses on his street still reminded me of wedding cakes. His blue door was still in need of painting. There was a new door knocker, in the shape of a fox. I only had to knock once. The door opened and there he was, smiling at me. His hair was still a big mop of unruly curls, a Fox family trait. He still wore glasses that could have come from a museum. His baggy, grubby clothes might have belonged to a gardener. Seeing him standing there, so familiar and so solid, I couldn’t help myself. I started to cry.

‘Ella.’ He held me tight, waited until my tears slowed, then took a step back. ‘Come in.’

If he was my aunt rather than my uncle, it would have been different, I’m sure. It would have been all talk, no silences. I’m so sad for you, Ella. You poor thing. How can you even begin to get over something like that? All the words I’d heard from so many people in the past twenty months, heard so many times that I couldn’t hear them any more. I hadn’t told the people around me in the winery in Margaret River what had happened, why I was there. I didn’t tell them that I was an editor, not a vineyard assistant turned restaurant kitchenhand. I could have got work in my own industry. I’d had many offers after word got around, but I needed everything to change. I couldn’t have any reminders of what my life had once been like.

Time and again, people who did know what had happened suggested that keeping busy would help the healing process. It’s not true, you know. Nothing helps. Because whatever I do with my body, my brain keeps ticking away, going over and over every second of that day, trying to find a new way of remembering, another way of changing what happened, winding itself into knots. That was – that is – the torture of it. Because it doesn’t matter how many times I examine it, how often I try to rewrite that day in my mind, the ending is the same. And no amount of physical work helps: outside pruning grapevines, rod-tying, picking grapes, or the work I did once I moved into the winery complex itself: washing floors, doing dishes, waitressing, being a kitchen assistant, working any shift on offer, doing overtime uncomplainingly, working the longest hours I could and spending any free time I had walking to tire myself out, to try to exhaust my body so my brain would have no choice but to sleep as well . . . Nothing works.

‘You look well,’ Lucas said.

He was being kind. I knew I looked exhausted. I probably had mascara all over my face now too. I tried to smile. ‘You too. Have you been working out?’

It was an old joke between us – Lucas would sooner fly to the moon than go to a gym. He grinned, running his fingers through his curls, ruffling them more than usual. He always did that when attention turned to him. I imagined he was like that at the university too, tousling his hair during his lectures, getting closer to the image of a mad history professor with every sentence.

‘I like the jumper,’ I said. It was a jumper I’d knitted – tried to knit for him – twenty-one years ago, when I was thirteen.

I’d found the pattern in an old magazine and got our next-door neighbour to teach me how to make it. It was supposed to have a design of a fox – of course – on the front. I made a mess of it, unpicking and reknitting it so many times that each strand of wool was covered in grime from my increasingly sweaty fingers. I had trouble with the sleeves and the turn-down collar, and as for the fox design . . . By the time I finished, the creature on the front looked more like E. T. than a fox. But I proudly sent it off, wrapped in Christmas paper. In return, Lucas not only sent me a fax telling me how much he loved it and how warm it was, he also sent a photo of himself wearing it. Charlie had taken a great interest in the photo. He kindly said nothing about the jumper’s design, but focused on Lucas himself. It was the first time he’d seen a photo of him. ‘Does he look like your dad? Like your dad would if he was alive, I mean.’

Lucas and my dad had been very alike. Charlie was right, I realised. I now had an idea of what my dad would have looked like if he hadn’t gone off to Canada and got killed.

I noticed Mum picking up the photo too, but she didn’t say anything to me about Lucas’s similarity to Dad. She did say something to me about the fox resembling an alien, though.

‘Never mind. Practice makes perfect,’ Walter said. ‘You could try to do a jumper for Jess next.’

‘No thanks,’ I’d said. My knitting days were over.

‘I get offers for it every day,’ Lucas said now. ‘It’s a work of art.’

‘Art? That’s one word for it.’

I followed Lucas into his withdrawing room off the hallway. It was messier than ever.

‘Drink?’ he asked. ‘It’s night-time for you and your body clock, isn’t it?’

I shook my head. I’d stopped drinking alcohol. ‘But tea would be great, thanks.’

We went into the kitchen. It was filthy, every surface covered in dirty dishes, saucepans and plates. I tried not to react, or wince, when he pulled out two grubby cups from the crowded sink. When he reached for a milk jug that I could see had something like gravy on the side, I couldn’t stop myself.

‘Sorry, Lucas.’ I took the cups from him and washed them out, followed by the jug, followed by the kettle, and then, for good measure, I washed out the sink too. Lucas watched it all with a half smile. He’d never taken offence when I expressed disgust or astonishment at the squalor he and his students lived in. He just took a seat at the cluttered, dirty kitchen table – my fingers itched to clean it as well – watching me with his usual amused, affectionate expression.

‘It’s lovely to see you, Ella. I did miss having a maid.’

‘This house needs a bulldozer, not a maid.’

‘Speaking of which, how is your mother?’

‘Very well, thank you,’ I said, trying not to smile as I searched for a biscuit in one of the tins and found a few mouldy crumbs instead.

‘Still mad as ever, I suppose?’

I nodded.

‘And still famous?’

‘Getting more famous every day too.’ It was true. In the past six years, after a chance encounter with a TV crew in a Melbourne shopping centre, my mother had somehow become a household name in Australia. Walter was now her full-time manager. It was unfathomable to me. My mother had barely boiled an egg during my childhood. Now she was a celebrity TV chef.

‘Charlie seems as happy as ever in Boston.’

I nodded again. Charlie the happy house-husband, father of four and adored/adoring husband of Lucy, a sales representative for a medical company. They’d met when Charlie was seventeen and in the US as a Rotary exchange student. After becoming penpals, they’d met again when they were both in their mid-twenties and Lucy was visiting Australia. They’d fallen in love, married and immediately begun having children. Their youngest was four years old, the oldest nearly eleven. Lucy worked full-time while Charlie stayed at home, in an arrangement that suited them both.

‘I do enjoy his family reports,’ Lucas said. ‘Thank you for adding me to his mailing list. The one about the children at the dentist was like a comedy sketch.’

I couldn’t think of anything to say to that. I’d stopped reading Charlie’s weekly emails about his family. I was still in touch with Charlie about other things, of course. We emailed often, both of us carefully choosing our words, avoiding certain subjects. Charlie did all his communicating via computer, late at night, once the kids and Lucy were in bed. His family reports were only emailed to a few people – Walter, Mum, Jess, Lucas and me. They were his way of staying sane, he’d confessed to me once. They always had the same subject line, a play on words from Garrison Keillor’s Lake Wobegon stories. The original began: It’s been a quiet week in Lake Wobegon. Charlie’s was: It’s been a noisy week in Boston. I missed his stories of family life. But I couldn’t read them any more.

‘And Jess?’ Lucas asked. ‘How is she?’

At the sink, midway through pouring the boiling water, I stiffened.

He must have noticed. He waited a moment, then repeated his question.

I turned. ‘Lucas, I’m sorry. I can’t —’

He spoke again in the same calm tone. ‘Is she still writing her autobiography?’

I knew that piece of news about Jess years earlier had amused him. Jess had been writing her life story – in diary form – for the past six years, since she was sixteen years old. She’d always been convinced she’d be a musical theatre star one day. ‘I’ll be too busy when I’m famous to write anything, so I’m doing it now to save time,’ she’d told us all. She’d never been secretive about it, either. Other teenage girls probably hid their diaries from their families. Jess did formal readings from hers. They were written as she spoke, in a stream of consciousness. The title was the first line of each day’s diary entry: Hi, it’s Jess!

‘I don’t know,’ I said, not looking at him. It was the truth. I had no idea where Jess was or what she was doing. I’d asked my mother not to mention her. She’d eventually, reluctantly, agreed.

Lucas didn’t ask any more questions about her. Another reason to love him. An aunt might have kept on at me, as my mother had, many times. Please, Ella, she’s your little sister. Your family. You have to find a way to forgive her. You have to be able to move on somehow.

But how could I move on? Where was there for me to go?

There was one other person for Lucas to ask about. As I brought over the tea, I waited for him to mention Aidan. He didn’t. Not yet. But he would, I knew. I could almost feel Aidan’s presence in the kitchen between us. We’d met for the first time in here.

Lucas took a sip, pulled a face and put down his cup. ‘Ella, it’s terrible. The cup’s too clean.’

I swatted his arm affectionately, glad of the change in topic. Our conversation turned to general subjects, my flight, the London weather, his own work. Yes, he was very busy, as always, he told me. Yes, the house was still full of lodgers. Four at present, with a waiting list. Yes, they were all double-jobbing: PhD students by day, tutors by night. Geniuses in the making, all four of them.

One was a literature student, he said. ‘You’ll like her. Very cheerful girl. She has the most extraordinary hair. Bright pink one week, blue the next. You’ll have lots in common too, books, words, grammar —’

It wasn’t the time to tell him I’d given up editing. ‘She sounds great,’ I said.

‘And you and work, Ella? Any plans yet?’

It didn’t matter that I’d just stepped off a long flight. Lucas was always to the point like this. Another thing I loved about him. ‘No, not yet. I’ll register with some temp agencies tomorrow.’

‘Don’t.’

‘Don’t?’

‘Come and work for me again. You already know I pay well. Promptly, too.’

‘You don’t need to pay me. As soon as I finish this tea I’m going to scrub this place from top to bottom as a service to society.’

He smiled. ‘That’s not the kind of work I meant. And that’s not why I asked you to come to see me.’ He stood up, walked across the room and shut the door. When he returned and sat down opposite me, his expression was serious.

‘Ella, I need your help.’