Family Secrets, Christmas Letters, and Hello From The Gillespies

Years ago, a young Monica McInerney was working as a publicist on a book tour for Roald Dahl, a year before he died. She was in a hall filled with several hundred trembling school kids, all peering up at the towering author (he was almost two metres tall). As Dahl waited, one of the boys near her crept up to her microphone to ask the first question. He was quivering so much he could barely speak.

‘Um, Mr Dahl, my question is …’

‘Come on, we haven’t got all day!’ Dahl roared.

The tension in the room escalated, all eyes were downcast, the braver ones stealing fleeting glances.

‘Oh, well, Mr Dahl …’ the boy went on in his tiny voice, ‘um … what did you have for breakfast this morning?’

Dahl just stared. ‘What a ridiculous question,’ he barked. ‘What did I have for breakfast this morning? Oh, I mean honestly, what do you think I had for breakfast? I had whisky and cigarettes!’

Monica and the rest of the staff froze. The rest of the hall erupted. The kids loved it, and from then on they lined up enthusiastically to ask whatever question crossed their minds.

‘That was the magic of Roald Dahl,’ Monica says to me over the phone from her attic turned writing studio that looks out on an overcast Dublin sky. ‘Suddenly – onstage – there were his characters: the BFG, Miss Trunchbull. Talk about being true to yourself ! I learned a lot from him.’

I can’t help thinking that this encounter with one of the world’s greatest character creators influenced Monica’s writing later in life. Up to eight months before she writes a word, she tells me, the characters of her next family saga are clattering around in her head, bickering, chattering, and whispering secrets in each other’s ears.

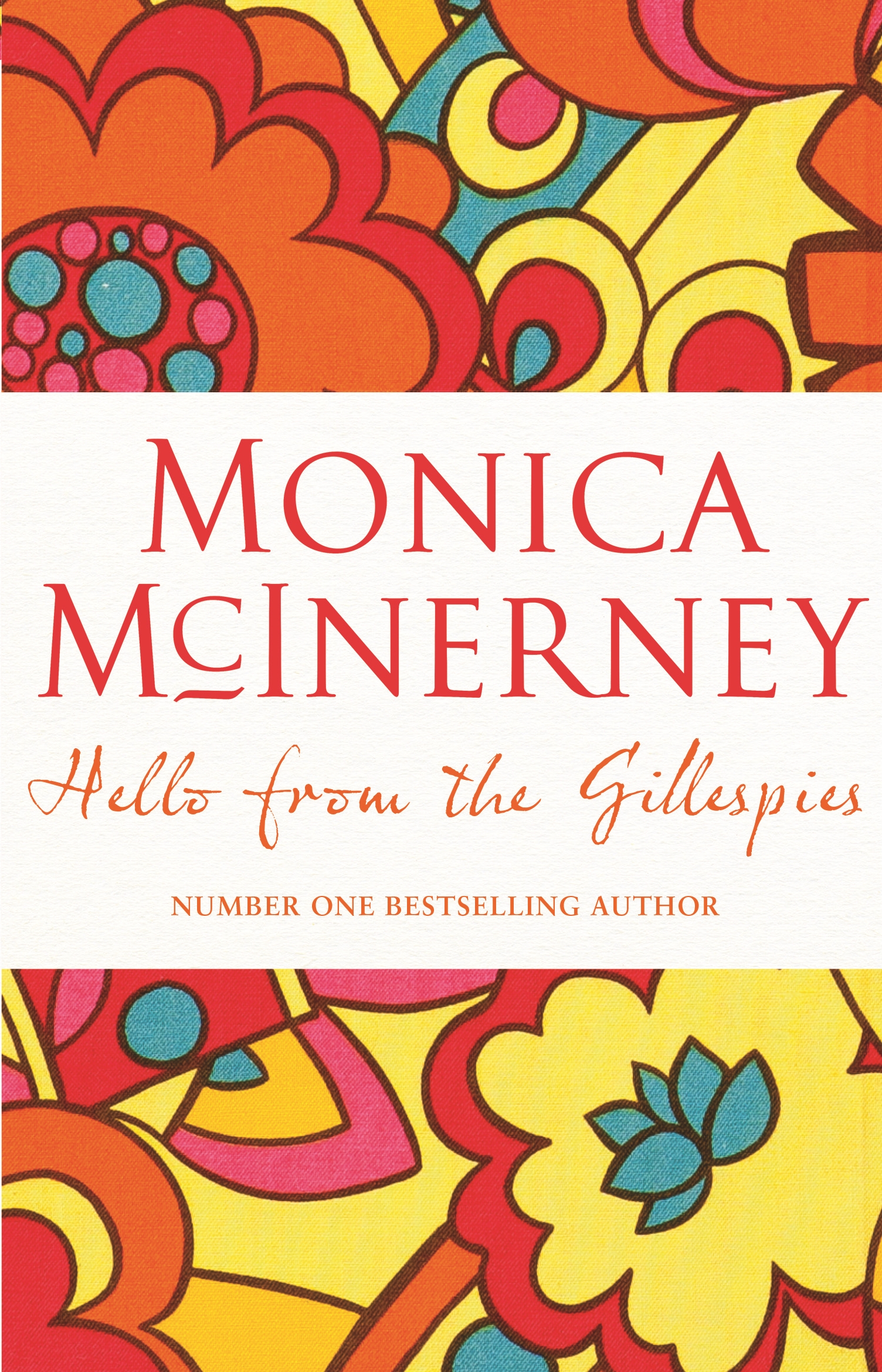

Angela, the leading lady of Hello from the Gillespies, is a young English rose who meets a lost Australian farmer, Nick Gillespie, when he wanders into the bar where she works. A few months later she leaves grey British streets in favour of the South Australian outback. Somewhere in this sparse wilderness lies Errigal, a huge sheep station owned by the Gillespie family for generations. We meet Angela three decades after her elopement to Errigal, as she sits down to write her yearly Christmas letter update.

‘I wanted to write about a woman who is reflecting on her past and wondering if she’s made the right decisions and is kind of losing sight of herself while trying to be a parent and wife at the same time. She was my starting point. One of the loveliest parts of the writing process for me is making characters all around her. I ask if she needed a husband, how many children they had, will I give her a friend? Bit by bit I started to populate my fictional family. She’s like the hub of the wheel, and the other characters are spokes coming off that.’

The Gillespie family is captained by Angela, the matriarch, and her husband, Nick, who is gradually becoming a research hermit as he obsessively retreats to the station’s office to pore over his investigations into the Gillespie ancestry. The couple have four children. Genevieve is a showbiz hairdresser who struts the streets of New York. Genevieve’s twin, Victoria, works in Sydney as a radio producer. When they’re not frenetically working, the twins are constantly on the phone to each other. Lindy, their younger sister, struggles with a swaying debt after an attempt to establish her own business goes awry. And then there’s Ig. At 10 years of age, he lives with Angela and Nick – after three successful escape attempts from boarding school.

Does Monica base any of her characters on her real relatives?

‘I don’t dare – they’d kill me!’ she laughs. ‘I grew up in a great, big, rambunctious family and we’re very close. I’m the middle of seven children. In terms of writing about the terrain of family life, I couldn’t have come from a better background. You’re the observer when you’re the middle child. I can put myself in different shoes.’

Growing up in the town of Clare, a few hours from the Flinders Ranges where Hello from the Gillespies is set, Monica remembers a squeaky gate that would announce the entrance of visitors to the family home. Would it be an aunt? A neighbour? Or maybe a friend rushing in to say, ‘You’d never believe what just happened!’ The gate would be opening and shutting all day, each screech heralding a new person and a new story.

Monica says that her stories are not autobiographical, but the emotions of family life in the books certainly are.

‘I write very emotional books. Everything that the characters feel I’ve felt in my own family. Great love and loyalty, anger, deep sadness and grief when my father died, and that’s what I draw on. Emotionally, they’re 100 percent autobiographical. But factually they’re not.’

Monica’s writing becomes a process of dropping ‘emotional explosions’ from up high and watching her characters scatter. ‘I’d read interviews with authors and they’d say “the character took over”, and I never understood what that meant until I started writing myself,’ she says. ‘It means that you’ve thought about them so much that they’re real to you – I know exactly how they’d react to anything. Even if a spaceship came and collected all the Gillesipes, I’d still know how each of those characters would react to finding themselves on Mars. The key is completely knowing the characters inside out.’

An interstellar journey would certainly give any family dynamic a bit of a stir, but the opening ‘explosion’ to the storyline of Hello from the Gillespies is just as disquieting. Imagine sitting down and writing out every family secret, every worry, and admitting things on paper that you don’t want to admit even to yourself. That’s what Angela does at the start of the book, instead of her Christmas letter. She does it just for herself, to clear her mind before she starts on the artificially cheery update she emails to the 100-plus people on her contact list. But what if those secrets got out?

Monica tells me that her mother used to receive dozens of ‘family update’ Christmas letters each year from friends. ‘These letters would arrive and I’d never believe that these perfect families existed. Everyone was always doing so well, everything would be marvellous, another promotion, straight-A exam results and so on. My family would sit passing them to each other, then we’d look around at each other and think, well, we’re a bit of a disaster aren’t we?’

When she was 17, a letter came in that was completely over the top. It inspired Monica and her sister to write a parody titled ‘The McInerney Report’. This report became a favourite Christmas activity for the next 10 years.

‘I’m absolutely sure that’s where this book came from, the fun I had writing these. Obviously they’re all make-believe and libellous and scandalous, but they were great fun. They’re so funny to read. I’ve still got a whole stack of them somewhere. If the house was on fire, that’s what I’d grab!’

The duplicity of these Christmas messages fascinates her. Monica’s writing often seeks out what lies behind people’s façades, the often unpleasant reality behind the confected optimism of a Christmas update.

‘I think people show a great vulnerability without realising it in those letters. It’s what they want people to know about them – and it’s never the truth. No family can escape grief and sadness and tension.

‘Every family is unique and everyone thinks everybody else’s family is perfect, but I’ve got this quote at the start of one of my books, The Faraday Girls. It’s a Chinese proverb: “Nobody’s family can hang out the sign: Nothing the matter here.” I love that quote. I could put it at the front of all of my books.’

(first featured in Good Reading Magazine)